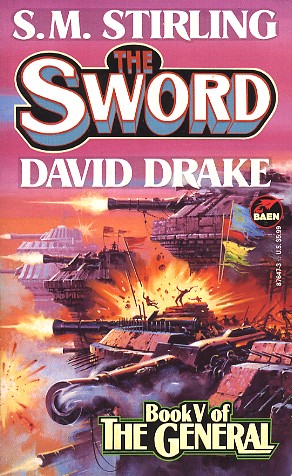

Книга: The Sword

The Sword

The General

Book V

S.M. Stirling & David Drake

CONTENT

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Dedication

To Jan

Chapter One

"Raj?" Thom Poplanich muttered.

Then, slowly: "Raj, how old are you?"

Raj Whitehall managed a smile. "Thirty," he said.

The perfect mirrored sphere of Sector Command and Control Unit AZ12-b14-c000 Mk. XIV's central . . . being . . . showed an image which seemed to give the lie to that. It wasn't the gray hairs or the scars on the backs of his hands that made him seem at least forty, or ageless.

It was the eyes.

Thom looked at his own image. Nothing at all had changed since that moment when he'd frozen into immobility, five years ago. Not the unhealed shaving nick on his thin olive cheek, or the tear in his floppy tweed trousers from a revolver bullet.

Life is change, Center said. The voice of the ancient computer was like their own thoughts, but with a vibrato overtone that somehow carried a sense of immense weight like a pressure against the film of consciousness. Even I change.

Raj and Thom looked up, startled. "Center? You're alive?" Thom asked.

No words whispered in their skull. Thom looked at his friend. Raj looks like an old man.

I haven't changed a hair, outwardly . . . but that's the least of it. Five years of mental communion with the machine that held all Mankind's accumulated knowledge. Five years, or eternity. He thought of his life before that day, and it was . . . unimaginable. Less real than the scenarios Center could spin from webs of data and stochastic analysis.

The two men gripped forearms, then exchanged the embrahzo of close friends. Thom could smell coal-smoke and gun-oil on the wool of his friend's uniform jacket, that and riding dogs and Suzette Whitehall's sambuca jasmine perfume.

The scents cut through the icy certainties Center's teaching had implanted in his mind. Unshed tears prickled at his eyes as he held the bigger man at arm's length.

"It's good to see you again, my friend," he said quietly.

"Yes, that's . . . well, I came to say goodbye."

"Goodbye?" Thom asked sharply.

"That's right," Raj said, turning slightly away. His eyes moved across the perfect mirrored surface of the sphere, that impossibly reflected without distorting. "Things . . . well, Cabot Clerett, the Governor's nephew" —and heir, they both knew— "was along on the campaign. There were a number of difficulties, and he, ah, was killed."

"Spirit of Man of the Stars," Thom blurted. "You came back to East Residence after that? Barholm was suspicious of you anyway."

Raj gave a small crooked smile and shrugged. "I didn't reconquer the Southern and Western Territories for the Civil Government just to set myself up as a warlord," he said. "Center said that would be worse for civilization than if I'd never lived at all."

An oversimplification but accurate to within 93%, ±2, Center added remorselessly. Over the years their minds had learned subtlety in interpreting that voice; there was a tinge of . . . not pity, but perhaps compassion to it now. The long-term prospects for restoration of the federation, here on Bellevue and eventually elsewhere in the human-settled galaxy, required Raj Whitehall's submission to the civil authorities. Too many generals have seized the chair by force.

Thom nodded. The process had started long before Bellevue was isolated by the destruction of its Tanaki Spatial Displacement net. The Federation had been slagging down in civil wars for a generation before that, biting out its own guts like a brain-shot sauroid. The process had continued here in the thousand-odd years since, and according to Center everywhere else in the human-settled galaxy as well.

"Couldn't Lady Anne do something?" he asked. Barholm's consort was a close friend of Raj's wife Suzette, had been since Anne was merely the . . . entertainer was the polite phrase . . . that young Barholm had unaccountably married despite being the Governor's nephew. The other court ladies had turned a cold shoulder back before Barholm assumed the Chair; Suzette hadn't.

"She died four months ago," Raj said. "Cancer."

A brief flash of vision: a canopied bed, with the incense of the Star priests around it and the drone of their prayers. A woman lying motionless, flesh fallen in on the strong handsome bones of her face, hair a white cloud on the pillow with only a few streaks of its mahogany red left. Suzette Whitehall sat at the bedside, one hand gripping the ivory colored claw-hand of her dying friend. Her face was an expressionless mask, but slow tears ran from the slanted green eyes and dripped down on the priceless snowy torofib of the sheets.

"Damn," Thom said. "I know she wanted every Poplanich dead, but . . . well, Anne had twice Barholm's guts, and she was loyal to her friends, at least."

Raj nodded. "It was right after that that I was suspended from my last posting—Inspector-General—and my properties confiscated. Chancellor Tzetzas handled it personally."

"That . . . that . . . he gives graft a bad name," Thom spat.

Raj smiled wanly. "Yes, if the Chancellor didn't hate me, I'd wonder what I was doing wrong."

A flash from Center; a tall thin man in a bureaucrat's court robe sitting at a desk. The room was quietly elegant, dark, silent; a cigarette in a holder of carved sauroid ivory rested in one slim-fingered hand. He signed a heavy parchment, dusted the ink with fine sand, and smiled. A secretary sprang forward to melt wax for the seal . . .

Raj nodded. "I expect to be arrested at the levee this afternoon. Barholm's worried—"

Thom laid a hand on Raj's shoulder. The muscle under the wool jacket was like india rubber. It quivered with tension.

"You should make yourself Governor, Raj," he said quietly. "Spirit knows, you couldn't be worse than Barholm and his cronies."

Raj smiled, but he shook his head. "Thanks, Thom—but if I have a gift for command, it's only for soldiers. Civilians . . . I couldn't get three of them to follow me into a whorehouse with an offer of free drinks and pussy. Not unless I had a squad behind them with bayonets; and you can't govern that way, not for long. I'd smash the machinery trying to make it work. Barholm is a son-of-a-bitch, but he's a smart one. He knows how to stroke the bureaucracy and keep the nobility satisfied, and he really is binding the Civil Government together with his railroads and law reforms . . . granted a lot of his hangers-on are getting rich in the process, but it's working. I couldn't do it. Not so's it'd last past my lifetime."

Observe:

* * *

—and they saw Raj Whitehall on a throne of gold and diamond, and men of races they'd never heard of knelt before him with tribute and gifts . . .

. . . and he lay ancient and white-haired in a vast silken bed. Muffled chanting came from outside the window, and a priest prayed quietly. A few elderly officers wept, but the younger ones eyed each other with undisguised hunger, waiting for the old king to die.

One bent and spoke in his ear. "Who?" he said. "Who do you leave the keyboard and the power to?"

The ancient Raj's lips moved. The officer turned and spoke loudly, drowning out the whisper: "He says, to the strongest."

Armies clashed, in identical green uniforms and carrying Raj Whitehall's banner. Cities burned. At last there was a peaceful green mound that only the outline of the land showed had once been the Gubernatorial Palace in East Residence. Two men worked in companionable silence by a campfire, clad only in loincloths of tanned hide. One was chipping a spearpoint from a piece of an ancient window, the shaft and binding thongs ready to hand. His fingers moved with sure skill, using a bone anvil and striker to spall long flakes from the green glass. His comrade worked with equal artistry, butchering a carcass with a heavy hammerstone and slivers of flint. It took a moment to realize that the body had once been human.

* * *

Raj shivered. That was the logical endpoint of the cycle of collapse here on Bellevue, and throughout what had once been the Federation; if it wasn't prevented, there would be savagery for fifteen thousand years before a new civilization arose. The image had haunted him since Center first showed it. It felt true.

"Spirit knows, I don't want Barholm's job," he went on. "I like to do what I do well, and that isn't my area of expertise. The problem is getting Barholm to understand that."

Barholm's data gives him substantial reason for apprehension, Center pointed out. Not only does Raj Whitehall have the prestige of constant victory, but more than sixteen battalions of the civil government's cavalry are now comprised of ex-prisoners from the former military governments.

Squadrones and Brigaderos; Namerique-speaking barbarians, descendants of Federation troops gone savage up in the desolate Base Area of the far northwest. They'd swept down and taken over huge chunks of the Civil Government, imposing their rule and their heretical Spirit of Man of This Earth cult on the population. Nobody had been able to do anything about it . . . until Barholm sent Raj Whitehall to reconquer the barbarian realms of the Military Governments.

Governor Barholm had officially proclaimed Raj the Sword of the Spirit of Man. The prisoners who'd volunteered to serve the Civil Government had seen him in operation from both sides. They believed that title.

"Then stay here!" Thom said. "Center can hold you in stasis, like me—hold you until Barholm's dust and bones. You've done all you can, you've done your duty, now you deserve something for yourself. It won't further the reunification of Bellevue for you to commit suicide!"

Probability of furthering the restoration of the federation is slightly increased if Raj Whitehall attends the levee, Center said.

"I must go. I must. I—"

Raj turned back, and Thom recoiled a half step. The other man's teeth were showing, and a muscle twitched on one cheek. "I . . . there's been so much dying . . . I can't . . . so many dead, so many, how can I save myself?"

"They were enemies," Thom said softly.

"No! Not them. My own men! I used men like bullets! There aren't one in three of the 5th Descott Guards remaining, of the ones who rode out with me against the Colony five years ago. Poplanich's Own—raised from your family estates, Thom—had a hundred and fifty casualties in one battle, and I was leading them."

Thom opened his mouth, then closed it again. Center cut in on them, an iron impatience in its non-voice:

Leading is the operative word, Raj Whitehall. You were leading them. Observe:

* * *

"Back one step and volley!" Raj shouted, hoarse with smoke and dust.

Around him the shattered ranks firmed. Colonial dragoons in crimson djellabas rode forward, reins in their teeth as they worked the levers of their repeating carbines. The muzzles of their dogs snaked forward, then recoiled from the line of bayonets.

BAM. Ragged, but the men were firing in unison.

"Back one step and volley!" Raj shouted again.

He fired his revolver between two of the troopers, into the face of a Colonial officer who yipped and waved his yataghan behind the line of dragoons. The carbines snapped, and the man beside Raj stumbled back, moaning and pawing at the shattered jaw that dangled on his breast.

"Hold hard, 5th Descott! Back one step and volley."

* * *

Raj blinked back to an awareness of the polished sphere that was Center's physical being. That had been too vivid: not just the holographic image that the ancient computer projected on his retina; he could still smell the gunpowder and blood.

If you had not struck swiftly and hard, the wars would have dragged on for years. Deaths would have been a whole order of magnitude greater, among soldiers of both sides and among the civilians. As well, entire provinces would be so devastated as to be unable to sustain civilized life.

Images flitted through their minds: bones resting in a ditch, hair still fluttering from the skulls of a mother and child; skeletal corpses slithering over each other as men threw them on a plague-cart and dragged it away down the empty streets of a besieged city; a room of hollow-eyed soldiers resting on straw pallets slimed with the liquid feces of cholera.

"That's true enough for a computer," Raj said.

Even then, Thom noted the irony. He was East Residence born, a city patrician, and back when they both believed computer meant angel he'd doubted their very existence. That had shocked Raj's pious country-squire soul; Raj never doubted the Personal Computer that watched over every faithful soul, and the great Mainframes that sat in glory around the Spirit of Man of the Stars. Now they were both agents of such a being.

Raj's voice grew loud for a moment. "That's true enough for the Spirit of Man of the Stars made manifest, true enough for God. I'm not God, I'm just a man—and I've done the Spirit's work without flinching. But I'd be less than a man if I didn't think I deserve death for it." Silence fell.

"They ought to hate me," he whispered, his eyes still seeing visions without need of Center's holographs. "I've left the bones of my men all the way from the Drangosh to Carson Barracks, across half a world . . . they ought to hate my guts."

They do not, Center said. Instead-

* * *

A group of men swaggered into an East Residence bar, down the stairs from the street and under the iron brackets of the lights, into air thick with tobacco and sweat and the fumes of cheap wine and tekkila. Like most of those inside, they wore cavalry-trooper uniforms—it was not a dive where a civilian would have had a long life expectancy—but most of theirs carried the shoulder-flashes of the 5th Descott Guards, and they wore the red-and-white checked neckerchiefs that were an unofficial blazon in that unit. They were dark close-coupled stocky-muscular men, like most Descotters; with them were troopers from half a dozen other units, some of them blond giants with long hair knotted on the sides of their heads.

There was a general slither of chairs on floors as the newcomers took over the best seats. One Life Guard trooper who was slow about vacating his chair was dumped unceremoniously on the sanded floor; half a dozen sets of eyes tracked him like gun turrets turning as he came up cursing and reaching for the knife in his boot. The Life Guardsman looked over his shoulder, calculated odds, and pushed out of the room. The hard-eyed girl who'd been with him hung over the shoulder of the chair's new occupant. The men hung their sword belts on the backs of their chairs and called for service.

"T'Messer Raj," one said, raising a glass. "While 'e's been a-leadin' us, nivver a one's been shot runnin' away!"

* * *

- They do not hate you. They fear you, for they know you will expend them without hesitation if necessary. But they know Raj Whitehall will lead from the front, and that with him they have conquered the world.

"Then they're fools," Raj said flatly.

"They're men," Thom said. "All men die, whether they go for soldiers or not. But maybe you've given them something that makes the life worth it, just as you have Center's Plan to rebuild civilization throughout the universe."

They exchanged the embrahzo again. Thom stepped back and froze, his body once again in Center's timeless stasis.

Raj turned and took a deep breath. "Can't die deader than dead," he murmured to himself.

Chapter Two

The great corridor outside the Audience Hall shone with the delicate colored marble and semiprecious stone that made up the intaglio work of the floor. The walls were arched windows on the outer side, and religious murals on the inner—icons of the Saints, lives of the martyrs, stars, starships, Computers calling forth Order from Primeval Chaos. Though the day was overcast, hidden gaslights threw a bright radiance through mirrors.

Soldiers in the black uniforms and black breastplates of the Life Guards stood along the walls every few paces, rifles at port; officers had their swords drawn and the points resting at their boots. The uniforms were Capital-crisp, but the faces under the plumed helmets were closed and watchful—square beak-nosed faces, dark and hard, on men slightly bowlegged from riding as soon as they could walk. The Life Guards were recruited from the Barholm family estates back in Descott county, from vakaros and yeoman-tenant rancheros. When Descotters ate a man's salt they took the responsibilities seriously, in the main.

Suzette adjusted Raj's cravat, beneath the high wing collar of the dress-uniform jacket. There was a fixed, intent look on her face. Raj recognized it; it was the look you got when the overall situation was completely out of control, so you focused on the immediate skill you could master. Suzette had been brought up in East Residence, and her family had been patrician for fourteen generations. Court etiquette—and the intricate currents of court intrigue—were as much her heritage as the saddle of a war-dog or the hilt of a saber were to him.

He'd seen the same look on a Brigade trooper's face, adjusting the grip on his sword and the angle of the blade—as he rode into the muzzle of a cannon loaded with grapeshot.

Three of his Companions were standing around, with similar expressions. They were looking at the Life Guards, and figuring the odds on a firefight if an order came through to arrest Raj on the spot. Not good, he thought.

"Relax," he said quietly. "There isn't going to be any trouble here today."

The party around Raj Whitehall stood in a bubble of social space, lower-ranking courtiers and messengers either avoiding their eyes or staring fascinated at the famous General Whitehall; for the last time, if rumor was correct. Many of them were probably thinking how lucky they were never to have risen so high. The stalk that stood out above the others was the first to be lopped off.

Which is why the Civil Government doesn't rule the whole Earth, as it should, Raj thought with an old, cold anger.

Correct, Center replied. Then it added pedantically: Bellevue. Earth will come later.

The crowd parted as a man came through. He wasn't particularly imposing; no more than twenty-one or so, and slimly handsome. His left arm ended at a leather cup and steel hook where the hand should have been. His uniform was standard issue for Civil Government cavalry, blue swallowtail coat and loose maroon breeches, crimson sash under the Sam Browne belt; all tailored with foppish care, but travel-worn and stained with sea salt in places. He carried his round bowl helmet with the chainmail neck-guard and twin captain's stars tucked under his left arm. The right fist snapped to his chest as he saluted, then bowed to Suzette.

"Messer Raj," he said. "My lady Whitehall." A smile as he glanced past them to the other Companions. "Dog-brothers."

"Spirit," Raj said mildly, shaken out of his strait preoccupation with what would probably happen in the next half-hour. "I thought you were back in the Western Territories with the 5th, Bartin."

Not to mention with Colonel Gerrin Staenbridge; Bartin Foley had gotten into the 5th as Gerrin's protégé-cum-boyfriend. He was far more than that now, of course.

"Administrator Historiomo decided," the young officer said, voice carefully neutral, "that since the Brigade survivors in the Western Territories were cooperating fully, a number of units were surplus to garrison needs."

"Which units?" Raj said.

Bartin cleared his throat. "The 5th Descott Guards," he said.

Raj's Own, as they liked to call themselves.

"The 7th Descott Rangers, 1st Rogor Slashers, Poplanich's Own, and the 18th Komar Borderers," he went on.

The cavalry units most closely associated with Raj, and the ones commanded by the men who'd become his Companions, the elite group of close comrades he relied on most.

"In addition, the 17th Kenden County Foot, and the 24th Valencia," he continued.

Jorg Menyez commanded the 17th: a Companion, and the Civil Government's best infantry specialist, able to turn the despised foot soldiers into fighting men of sorts. The 24th . . . Ferdihando Felasquez. Good man . . .

"And last but not least, the 1st and 2nd Mounted Cruisers."

Recruited from the defeated barbarians of the Squadron, after Raj crushed them in a single month's campaign back in the Southern Territories, three years ago. They'd always been warriors; under civilized instruction, they'd also become quite capable soldiers. The commander of the 1st Cruisers, Ludwig Bellamy, had made the same transition; but as a Squadrone nobleman he also regarded himself as Raj's personal liegeman. Tejan M'Brust, the Descotter Companion who'd taken over the 2nd Cruisers, probably thought the same way—although he wasn't supposed to, being a civilized man.

"They're all," Bartin went on, with a slight smile, bowing over Suzette's hand, "on their way back. Together with the field artillery. I came ahead on one of the steam rams, but everyone should be here in a day or three, if the weather stays fine."

Beside Raj, Colonel Dinnalsyn pricked up his ears. The artillery specialist had hated being separated from his beloved weapons. He'd trained those crews himself.

Joy, Raj thought. It just happened to look like Raj's own personal army was heading back to the East Residence at flank speed.

Antin M'lewis cracked his fingers. "What happen t'Chivrez?"

The Honorable Fedherko Chivrez had been sent out to take command of the Western Territories after Raj conquered them—and had arrived to find the Governor's promising young heir Cabot Clerett dead at Raj's feet, with a smoking carbine in Raj's hand.

Suzette gave him a single cool violet look from her slanted eyes and then turned them away, her face the unreadable mask of an East Residence aristocrat.

Raj remembered Cabot's eyes bulging, as Suzette shot him neatly behind the ear, in the instant before his trigger finger would have punched an 11mm pistol round through Raj's body. Chivrez had seen; Chivrez had been Director of Supply in Komar back five years ago, and had tried to withhold supplies from Raj's men. Two Companions named Evrard and Kaltin Gruder had run him out a closed window headfirst, then held him while Antin M'lewis started to flay him from the feet up. Raj had gotten the supplies and won the campaign.

The trouble with that sort of method was the long-term problems. On the other hand, if Raj hadn't gotten those supplies, his troops would have been wiped out by the Colonials in the desert fighting. You paced yourself to the task, and if the task got done you worried about secondary consequences later.

"Ah." Bartin Foley considered the tip of his hook. "Well, Messer Chivrez seems to have betrayed the Governor's trust and absconded with some of the Brigade's treasures."

Observe, Center said.

A bedroom in the palace of the Generals of the Brigade, in the Western Territories. Chivrez thrashing, his arms and legs held down by four strong men, another pressing a pillow over his face. The stubby limbs thrashed against the bedclothes. After a few minutes they grew still; Ludwig Bellamy wrapped the body in the sheets and hoisted it. Even masked, Raj recognized Gerrin Staenbridge as the one holding open the door.

The scene shifted, to the swamps outside Carson Barracks. The same men tipped a burlap-wrapped bundle off the deck of a small boat. It vanished with scarcely a splash, weighed down with lengths of chain and a cast-iron roundshot weighing forty kilos. Gerrin raised a meter-diameter blazon of the Brigade's sunburst banner, crafted in silver and gold with the double lightning flash across it picked out in diamond.

"Pity," he murmured. "Not bad work in a garish sort of barbarian way, and it would buy a good many opera tickets and dinners at the Centoyard back home. Ah, well—authenticity."

He tossed the disk after the bureaucrat's body. It sank with a popping bubble of marsh gas. Somewhere off in the swamps a hadrosauroid bellowed.

* * *

Antin M'lewis grinned uneasily as the Companions exchanged glances. They knew, of course . . . but he wasn't quite sure if Messer Raj knew. They were all of the Messer class by birth themselves; he'd levered himself up into it by hitching his star to Messer Raj's wagon. Ye takes t'risk a' fallin', too, he thought.

M'lewis had started off as a Bufford Parish bandit, a sheep stealer by hereditary profession, and made even that most lawless part of not-very-lawful Descott County too hot for him. Enlistment had been the alternative to a rope—or a less formal appointment with a knife. He'd met Raj over a little matter of a peasant's pig gone missing despite a no-foraging order. One look had told him this was a man who had to be either served or killed, and he'd made his decision. It had led him near enough to death more times than he could count, and also to advancement beyond his dreams.

On the other hand, one of the things that surprised him about gentlemen born was how bad they were at making use of their advantages. There were good points to a rough upbringing. One of them was being able to say the unsayable.

"Ah, ser," he suggested, leaning forward and whispering, "what wit' t' lads comin' in s'soon, mebbe we'uns ud better dip out loik—come back wit' better company inna day er two?"

Raj spoke in a clear, conversational tone, without looking around: "I'm attending this levee as ordered by the Sovereign Mighty Lord, Captain M'lewis. You may do as you please."

M'lewis spat on the intaglio floor. Spirit. Mebbe I should a' stayed in sheep-stealin'.

He followed nonetheless; he might have been born a thief, but he'd eaten this man's bread and salt.

A metal-shod staff thumped the floor, and the tall bronze panels of the Audience Hall swung open. The gorgeously robed figure of the Janitor—the Court Usher—bowed and held out his staff, topped by the Star symbol of the Civil Government.

Suzette took Raj's arm. The Companions fell in behind him, unconsciously forming a column of twos. A Life Guard officer stepped forward.

"Your weapons, Messers," he said, his face expressionless.

Raj made a chopping gesture with his free hand, and the forward rustle of the Companions died. He handed over ceremonial revolver and court sword. This time it was Bartin Foley who whispered in his ear:

"A company of the 5th arrived with me, sir. If you're arrested . . ."

"Captain Foley, the Sovereign Mighty Lord's orders will be obeyed by all troops under my command—is that clear?"

Observe, Center whispered in his mind. Raj, in a cell, darkness and the flickering light of lanterns. Rifle-fire from the halls outside, flat slapping echoes off the stone, and the turnkey's shotgun pointed through the bars at Raj's face, the hammer falling as he jerked the trigger . . .

"I've served my Governor and the Spirit of Man to the best of my ability," Raj added. "I chose to assume that the Governor, upon whom be the blessings of the Spirit always, will see it the same way."

The functionary's voice boomed out with trained precision through the gold-and-niello speaking trumpet:

"General the Honorable Messer Raj Ammenda Halgern da Luis Whitehall, Whitehall of Hillchapel, Hereditary Supervisor of Smythe Parish, Descott County! His Lady, Suzette Emmaenelle—" None of his other titles, Raj noted. He'd been officially hailed Sword of the Spirit of Man and Savior of the State in this room.

He ignored the noise, ignored the brilliantly decked crowds who waited on either side of the carpeted central aisle, the smells of polished metal, sweet incense, and sweat. The Audience Hall was two hundred meters long and fifty high, its arched ceiling a mosaic showing the wheeling galaxy with the Spirit of Man rising head and shoulders behind it. The huge dark eyes were full of stars themselves, staring down into your soul.

Along the walls were automatons, dressed in the tight uniforms worn by Terran Federation soldiers twelve hundred years before. They whirred and clanked to attention, powered by hidden compressed-air conduits, bringing their archaic and quite non-functional battle lasers to salute. The Guard troopers along the aisle brought their entirely functional rifles up in the same gesture.

The far end of the audience chamber was a hemisphere plated with burnished gold, lit via mirrors from hidden arcs. It glowed with a blinding aura, strobing slightly. The Chair itself stood four meters in the air on a pillar of fretted silver, the focus of light and mirrors and every eye in the giant room. The man enChaired upon it sat with hieratic stiffness, light breaking in metallized splendor from his robes, the bejeweled Keyboard and Stylus in his hands. A tribal delegation was milling about before it, still speaking through its hired interpreter.

The linguist's face was professionally bland, but occasionally a look of horror would cross his features as he moved his lips, working out Sponglish equivalents of the mountaineers' singsong native tongue:

"Hjburni-burni-burni—"

"Humbly we beseech you, O Sovereign Mighty One, Sole Autocrat, our poverty prevents other than our traditional border auxiliary duties—"

Center broke in: more accurately rendered: back off, stonehouse-chief, or we'll see what terms the colony offers its border auxiliaries—we're closer to al Kebir than East Residence.

"Hjurni-burni-burni, burjimi murjimi urgimi—"

"In our humble huts in the mountains, we seek only to till our poor fields in peace—"

We're your allies and you pay us for guarding the passes;

"—kuljurni ablurni hjurni-burni Halvaardi burri murri—"

"—and surely there are closer, richer lands which need the attention of your talented administrators—"

—So the next tax collector who asks for "earth and water" from the Halvaardi gets thrown down a well to find plenty of both.

Barholm made a slight gesture with one hand, and the tribesfolk were ushered out, protesting, amid a ripe stink from the butter they used to grease their braids. One of the wooden clocks they carried on their belts gave its mechanical kuku, kuku as the pillar that supported the Chair sank toward the white marble steps; at the rear of the enclosure two full-scale statues of gorgosauroids rose to their three-meter height and roared as the seat of the Governor of the Civil Government sank home with a slight sigh of hydraulics. A faint whine sounded, and the arc lights blazed brighter. At the center of the mirrors' focus Barholm blazed like a shape of white fire.

Raj took three paces forward and went down in the ceremonial prostration—the full prostration, since his former titles were stripped from him. He rose and knelt the prescribed three times; by his side there was a quiet rustle of silks and lace as Suzette sank down with an infinite gracefulness.

"What punishment," Barholm boomed, his voice amplified by the superb acoustics of the Audience Hall, "is fit for him who was foremost in Our trust? Yea, what baseness is more base, what vileness more vile, than one into whose hand the Sword of the State has been entrusted—when that most wretched of men turns the Sword against the very root and foundation, the Coax Cable of the Spirit—"

In East Residence, rhetoric was the most admired of the arts—far ahead of, for instance, military or administrative skill; infinitely more so than engineering. A speech like this could go on for hours, when the entire content could be boiled down to "kill him."

The semicircle of high ministers stirred behind their desks. The tall slender form of Chancellor Tzetzas turned sharply to hiss General Gharzia, Commander of Eastern Forces, into silence; the elderly soldier was listening to a messenger—a courier in tight leathers, not a court usher or an aide. From the floor, Raj watched Gharzia's face congeal like cooling lard. He didn't have to pay attention to what Barholm said, he knew how that would end . . .

Gharzia rose and circled to Tzetzas' side. The Chancellor tried to shake off the hand that plucked at his sleeve, then turned to listen with a tight, controlled fury that would have frightened Raj if he'd been in Gharzia's shoes. People who seriously annoyed the Chancellor tended to have accidents, or develop severe stomach problems, or be killed in duels.

Raj had never seen Tzetzas frightened before. It was a far less pleasant experience than he would have thought; whatever his other vices, nobody had ever even accused the Chancellor of cowardice. To make him interrupt the ceremony of triumph over his most hated rival, it had to be something massive.

"And—" Barholm noticed the movement to his right and broke off, flipping up the smoked-glass eyeshield. "Tzetzas! What do you think you're doing?"

The raw fury in his voice made Tzetzas check half a step. The Governor was the Spirit's Viceregent on Earth; if he ordered the Guards to cut the Chancellor to pieces on the steps of the Chair, they would obey without hesitation. That had happened in past reigns, more than once. Wise Governors remembered that those reigns had been short . . . but Barholm Clerett had been growing more and more unstable since his wife died.

"Sovereign Mighty Lord," Tzetzas said, his voice a cool precision instrument, handled with faultless skill. "I deserve your anger for my boorishness. Yet concern drives your servant. The Colony has invaded our territories; news has arrived by heliograph."

There was a chain of stations between the frontiers and East Residence; high-priority messages could be relayed in hours, where couriers would take days or weeks. Only the Colony and the Civil Government possessed such means, on Bellevue.

"You interrupt me for a raid?"

The Bedouin and the Civil Government's Borderers had been stealing girls and sheep and cutting each other up over waterholes since time immemorial. It was a peaceful week that passed without a minor skirmish, and there were several razziah a year from either side. It usually didn't even cause a ripple in the profitable trade carried on between the more civilized urban element on both sides of the frontier.

Tzetzas threw himself down on his knees. "Not a raid, Sovereign Mighty Lord. Invasion. The Settler of the Colony himself, Ali—and his one-eyed brother and general, Tewfik. They have taken Gurnyca."

A low moan swept through the Audience Hall. That was the largest city on the lower Drangosh river and the closest major settlement to the eastern frontier.

The mad anger disappeared from Barholm's face, as cleanly as if cut with a knife. A minute later, so did the eye-hurting brilliance of the arc lights. By contrast, the Audience Hall seemed black.

"The levee is closed," Barholm said, in a flat carrying voice.

There were yelps of protest from petitioners. The officer of the Life Guards barked an order, and hands rattled on stocks as the rifles came to present-arms.

"An immediate meeting of the State Council will be held in the Negrin Room," Barholm said into the sudden stillness. "All others are dismissed."

Raj rose to one knee. "Sovereign Mighty Lord," he said calmly. "Does the Sole Autocrat wish my presence?"

Barholm paused, looking over his shoulder. "Of course," he said. A snarl broke through the mask of his face. "Of course!"

* * *

"Sayyida," the man said, bowing with hand to brows, lips and heart; his dress was the knee breeches and jacket of an East Residence bourgeois, but his tongue was the pure Syrian Arabic of Al Kebir, capital of the Colony. "Peace be with you."

"And upon you peace, Abdullah al'Aziz," Suzette Whitehall replied in the same language, the rolling gutturals falling easily from her tongue.

Her maids had replaced the split skirt, leggings, and blond wig of court formality with a noblewoman's day-robe; she wrote as she spoke, glancing up only occasionally. The steel nib of the pen skritched steadily on the paper.

"Are you ready?" she said.

"For the Great Game?" the Arab replied, smiling whitely in his neatly trimmed black beard. "Always, my lady."

"Good. Here are papers, and a sight-draft on Muzzaf Kerpatik."

The Whitehalls' chief steward, among other things. A Borderer from the southern city of Komar, and no friend of any Arab, but also not likely to let personal feelings interfere with his work.

"My instructions, sayyida?"

"Proceed at once to Sandoral on the Drangosh. Military intelligence for my lord, if it presents itself; for myself I wish full information on the higher officers of the garrison and the local nobles: loves, hates, histories, feuds, alliances. Also any information from the Colony."

He took the papers and repeated the bow, using the documents for added flourish. "I obey like those multiplex of wing and eye who served Sulieman bin'-Daud, my lady," he said cheerfully. "That city I know of old." He'd done similar work for her the last time Raj commanded in the East, four years before.

"See that nobody stuffs you into a bottle," she added dryly, dropping back into Sponglish.

"I shall be most careful," he replied in the Civil Government's tongue, faultless down to the capital-city middle-class crispness of his vowels. "There is yet much to be done to repay my debt to you, my lady. And," he added with a cold glint in his dark eyes, "to those Sunni sons of pigs in Al Kebir, also."

Druze were few on Bellevue; less, since the Settlers had decided to purify the House of Islam a generation ago. Those sniffed out by the mullahs could count themselves lucky to be sold as slaves to the sulfur mines of Gederosia. The path from there to Suzette Whitehall's household and manumission had been long and complex . . .

"Your family are provided for?" Abdullah nodded. "Go, then, thou Slave of God," Suzette said, once more in Arabic, playing on the literal meaning of the man's name. "Thy God and mine be with thee."

"And the Merciful, the Lovingkind with thee and thy lord, sayyida," he replied, and left.

"Fatima," Suzette went on.

"Messa?"

"Take this to the Renunciate Sister Conzwela Dihego; she's second administrative assistant for medical affairs to the Arch-Sysup of East Residence. It's an authorization to mobilize priest-doctors and medical nuns, with the necessary supplies and transport for immediate dispatch to Sandoral."

"Wasn't she with us in the Western Territories?" the Arab girl asked.

"Yes; and Anne got her that job on my say-so when we got back." Suzette sighed; she missed Anne. "Quickly. And send in Muzzaf."

The Companion sidled through the door as Fatima left; the opening showed a controlled chaos of packing. He was a short slight man, with the dark complexion of a Borderer and a singsong Komarite accent. He was dressed in jacket and breeches of white linen, the little peaked fore-and-aft cap of his region, and a sash which nearly concealed the pepperpot pistol and pearl-handled gravity knife he preferred. He bowed deeply, a gesture much like Abdullah's.

Nearly a thousand years of conflict had left the Borderers much resembling their enemies of the Colony, though it was a killing matter to suggest it aloud.

"Messa Whitehall," he said, showing white teeth against his spiked black chin-beard. Like everyone else in the household, he was reacting to the news of Raj's reinstatement with almost giddy relief. "We campaign again?"

"Yes," Suzette said.

She pushed a document across the table with a finger. "One of your relatives is contractor for the East Residence municipal coal yards, isn't he?"

Muzzaf nodded; men from Komar and the other Border cities were prominent in trade all over the Civil Government, and in the new joint-risk companies.

"Subcontractor, Messa. The primary contract is farmed to an . . . associate of Chancellor Tzetzas." He took up the paper and whistled silently. "That is a great deal of coal."

"Subcontractor is good enough. Have him release that amount to the Central Rail; and drop a suggestion with their dispatching agent that they begin to accumulate rolling stock immediately. Sweeten the suggestion if you have to."

"Immediately."

They exchanged a smile; Chancellor Tzetzas had confiscated all Raj's wealth . . . all that he had been able to find, at any rate. Neither the Chancellor nor Raj knew exactly how much the Whitehalls had had; Raj left such things to Muzzaf and Suzette . . . and they had anticipated the evil day long before. Raj knew how to handle guns and men, and even politics after a fashion, but money could also be a useful tool.

Silence fell as the steward left, broken only by the scritching of the pen and the faint thumps and scraping of the packing in the outer chambers. On the bed behind her were Raj's campaigning gear: plain issue swallowtail jacket of blue serge, maroon pants, boots, helmet, saber, pistol, map case, binoculars. Beside it was her linen riding costume and a captured Colonial repeating carbine, her own personal weapon . . . and the one, she reflected, that had disposed of the Clerett's heir.

A pity, she thought absently, tapping her lips with the tip of the pen before dipping the nib in the inkwell again. A very pleasant young man.

And easy to manipulate. Which had been crucial; like his uncle, he'd been mad with suspicion against Raj. With envy, too, in young Cabot's case: of Raj's reputation, his victories, his hold over his soldiers, and his wife.

A pity she'd had to kill him. Particularly just then. Shooting people was a crude emergency measure . . .

Which reminded her. She crossed to her jewel table and reached beneath for a small rosewood box. A tiny combination lock closed it, and she probed at that with a pin from a brooch.

Yes, the crystal vials of various liquids and powders within were all full and fresh—there was a slip of paper with a recent date inside to remind her, one of Abdullah's many talents.

You never knew what sort of help Raj would need . . . whether he knew it or not.

"You will triumph, my knight," she whispered to herself, closing the box with a click. "If I have anything to do with the matter."

Chapter Three

Governor Barholm stood while the servants stripped off the heavy robes; apart from Raj, they were the only people in the chamber who didn't look terrified . . . and they didn't have to watch the Governor's face. A sicklefoot had that sort of expression, just before it pivoted and slashed open its prey's belly with the four-inch dewclaw on one hind foot.

The Negrin Room was three centuries old. Walls were pale stone, traced over with delicate murals of reeds and flying dactosauroids and waterfowl; there was only one small Star, a token obeisance to religion as had been common in that impious age. The heads of the Ministries were there: Chancellor Tzetzas, of course; General Fiydel Klostermann, Master of Soldiers; Bernardinho Rivadavia, the Minister of Barbarians; Mihwel Berg of the Administrative Service; Gharzia, Commander of Eastern Forces. The courier from the east as well.

It was strange not to see Lady Anne Clerett, the Governor's wife. Barholm didn't have anyone he really trusted now that she was dead, and it was affecting his judgment.

"Heldeyz," Barholm snapped. "Give us the report, man."

Ministerial couriers were men of some rank themselves, but it was still strange how unintimidated Heldeyz looked, even facing the stark fury in Barholm Clerett's eyes. His own were fixed and distant, in a face still seamed by trail dust.

Barholm went on fretfully: "I don't know why Ali has done this. The treaty after the last war was generous to a fault—particularly since we won the war. The gifts of friendship . . ."

Observe:

* * *

Sweating slaves heaved at bundles of iron bars, heaping them on the flatbed rail-cars and lashing them down. One slipped and fell to the paving stones of East Residence's main station. A bar snapped across; as a clerk bustled over a guard rolled the broken end beneath his boot.

"Spirit," he said in a tone of mild curiosity. The interior of the fracture showed a gray texture. "That's not wrought iron, it's cast."

Cast iron came straight from the smelting furnace; it was hard, brittle and full of impurities. Only after treatment in a puddling mill did it become the ductile, easily worked material so valuable for machinery and tools.

The clerk cleared his throat. "I think you'll find," he said significantly, "that the Chancellor has inspected the manifests quite carefully."

The guard grinned; he was a thin man with a long nose and a pockmarked face, an East Residencer by birth with all the ingrained respect for a good swindle that marked that breed. He brushed his thumb over the first three fingers of his right hand. The clerk smiled back.

* * *

"Sovereign Mighty Lord," Raj said. "I think you'll find that quality, quantity, and delivery dates on our tribute—pardon, our gifts of friendship—to the Colony have been below the Treaty terms."

Figures scrolled before his eyes, and he read them in an emotionless monotone worthy of Center.

Barholm blinked. He turned his eyes on Tzetzas, and a fine beading of sweat broke out on the Chancellor's olive face. "Sole Autocrat," the minister said, spreading his hands. "When contracts are handed out, something always sticks—so many layers of oversight, so many hands—you know—"

The Governor's fist struck the table. Gold-rimmed kave cups bounced and clattered in their saucers.

"I know who's responsible for seeing that the payments were met!" he roared; suddenly there was the slightest trace of Descott County rasp in his Sponglish. "You fool, I don't expect you to work for your salary alone, but I did expect you to know enough not to piss in our own well! D'you have any idea what this war is going to cost in lost taxes and off-budget funding?"

He paused, and when he continued his voice was calm. "You'd better have some idea, because you're going to pay the overage—personally."

"Sovereign Mighty Lord," Raj said. "Right now, I think we'd better concern ourselves with the state of the garrisons on the Drangosh frontier."

Barholm snapped his fingers. "Gurnyca had a garrison of—"

"Ten thousand men, Sole Autocrat," Mihwel Berg said helpfully. "At least, ten thousand on the paybooks."

Chancellor Tzetzas busied himself with his papers. When Barholm spoke, it was to General Gharzia.

"General," he said, his voice soft and even, "tell me—and if you lie, it would be better for you if you had never been born—how many troops were actually on the strength of the Gurnyca garrison? In what condition?"

Gharzia licked his lips, going gray under the tanned olive of his skin. "Two thousand, Sovereign Mighty Lord. In . . . ah, poor condition."

Somebody had been collecting the pay of the missing eight thousand. All eyes turned to the Chancellor.

The ruler turned back to the courier from the east. "Now, Messer Heldeyz," he said evenly. "Your report, please."

"Yes, Sole Autocrat."

Heldeyz stared at his hands. "I met the Colonials fifty klicks south of Gurnyca," he began. "They—"

Observe, Center said:

* * *

Terrible as an army with banners. Bartin Foley had quoted that to Raj, once; it was a fragment of Old Namerique, from the codices that survived the Fall.

There were plenty of banners in the forefront of the Colonial host that crossed the Drangosh. The green flag of Islam, marked with the crescent, or with the house blazons of regiments and noble amirs. The peacock-tail of the Settlers; that meant Ali was present in person. And a black pennant marked with the Seal of Solomon in red. Tewfik. Ali's brother, disqualified from the Settler's throne because of the eye he'd lost in the Zanj Wars, but the Colony's right arm nonetheless.

Raj recognized the terrain instantly; he'd campaigned out east himself, five years ago. Generations of the Civil Government's soldiers had taken their blooding in that ghastly lunar landscape of eroded silt, and all too many left their bones there. Just north of the border and the river forts, by the look of it, in one of the locations where the right—the western—bank was too high for irrigation. In consequence nothing grew there, except for a few bluish-green native shrubs.

The oily-looking greenish-gray waters of the Drangosh were a kilometer and a half across. A bridge of boats had been built across it, big river-barges of the type used for trade up and down the river from Sandoral to Al Kebir and the far-off Colonial Gulf. Good engineering, Raj thought; as good as the Civil Government's army, or a little better. The barges were lashed together with huge sisal cables as thick as a man's waist; then timbers and planks were laid across to make a deck, and pounded clay half a meter thick on top of that to give the men and animals a firm surface. There were even straw balustrades on either side, chest high, to keep the beasts from spooking at the water curling up around the blunt prows of the barges.

Men flowed across in a steady stream: Colonial dragoon tabors, battalions, riding in column of fours, mainly. Mounted on slender Bazenjis and greyhounds, lever-action repeating carbines in scabbards by their right knees, scimitars or yataghans at their belts, bandoliers over the chests of their faded scarlet djellabas. The sun glittered on the polished spikes of their conical helmets, and the pugarees wound about them fluttered in the breeze. Between the blocks of cavalry came guns: light pompoms, quick-firers throwing a two-kilo shell from a clip magazine; field guns, much like the Civil Government's 75mms; and heavier pieces drawn by oxen. Those were cast-steel muzzle-loading rifles, heavy pieces up to 150mm, siege guns. And there was transport, light dog-drawn two-wheel carts, heavy wagons pulled by sixteen pair of oxen.

Officers directed the traffic with flourishes of their nine-tailed ceremonial whips, each thong tipped with a piece of jagged steel.

Where- Raj thought. Center's viewpoint shifted to the western bank.

In the Colony's army, as in the Civil Government's, infantry were usually second-line troops, good enough to hold forts and lines of communication. Ali—Tewfik, probably—had sent his over first, and they were hard at work. Swarms of men stripped to their loincloths or pantaloons, burned from their natural light brown to an almost black color, swinging picks and shoveling dirt into the baskets others hauled. They moved over the land like disciplined ants, and a pentagonal earthwork fortress was rising around the western end of the pontoon bridge. A fairly formidable one, too; deep ditch, ten-meter walls, ravelins and bastions at the corners with deep V-notches for the muzzles of the guns. The Colony's green flag and the Settler's peacock already flapped around a huge pavilion-tent in its center. Within, ditched roadways had been laid out, and neat rows of pup tents, heaps of stores, and picket-lines for the dogs were rising.

Enough for-

* * *

"Sixty thousand men," Raj said. "Fifty thousand cavalry, ten thousand infantry or a little more to hold the bridgehead."

Heldeyz stopped, flustered. "Yes, heneralissimo," he said; evidently the news of Raj's demotion hadn't reached the eastern marches yet. "That's my estimate. How did you know?"

"Logistics. If Ali's planning on moving as far north as Sandoral, that's the maximum number he can supply overland from the bridgehead. Our forts at the border can hold out for six months or more, even if the Colony put in a full attack—which they won't or they couldn't put that large a field army into action. They'll have blockforces around the frontier strongpoints, but they can't use river transport to supply Ali. So they moved north and crossed upstream of the forts."

Both the Colony and the Civil Government had put generations of effort into those defenses. The giant cast-steel rifles in the forts would smash anything that tried to steam past them on the river. That ruled out supply by riverboat.

"Ali—Tewfik—must have built a railroad line to the east bank," Raj said. "But on the western shore, it'll be animal transport. Even with what they can forage, no more than fifty thousand men and riding dogs. They wouldn't bring less, not for a full-scale invasion, and they couldn't feed more."

Barholm shot Raj a considering look. "Go on," he said to Heldeyz.

The courier nodded. "I met—"

Observe, Center whispered in Raj's mind:

* * *

Heldeyz knelt before a throne. It was lightly built, of cast bronze fretwork, but inlaid with gold and gems in a pattern that flared out behind the seat like a peacock's tail. A man in shimmering cloth-of-gold sat on it. Throne and man glittered when stray beams of light penetrated the lacework canopy that slaves held above it; a spray of peacock feathers sprang from the great ruby in the clasp at the front of his turban. Around the Settler stood generals and noblemen, a few Bedouin chiefs in goathair robes and ha'ik, mullahs in black, servants with flasks of iced sherbert, crouching clerks and accountants with paper and pen and abacus. None of them came within the ring of guardsmen, black slave-mamluks with great curved swords naked in their hands, or bell-mouthed riot guns at the ready.

"Your master, the kaphar king, has offended me grievously," Ali said, speaking fair Sponglish. "He has violated the terms of our treaty . . . and my father's blood cries out for vengeance. No duty is more sacred. Yet Allah, the Merciful, the Lovingkind, enjoins us to peaceful deeds."

Ali's face was heavy-featured but regular, the curved beak of the nose dominating, offset by full red lips and a forked beard. His eyes were large and brown, luminous and somehow disturbing. Apart from an occasional twitching tic of his right cheek, the expression was one of mild reason.

An officer approached, going down on both knees and bowing until the point of his helmet-spike touched the glowing Al Kebir carpets that covered the ground before the Settler's pavilion and campaign-throne.

"Amir el Mumineen, Commander of the Faithful, the infidel emissaries from the city of Gurnyca crave the honor of your presence."

Ali's eyebrows rose slightly. He leaned back in the portable throne, and servants stepped forward to spray rosewater from crystal ewers through rubber bulbs. He sipped sherbert from a glass globe through a silver straw and waited.

"By all means, let them enter," he said gently.

The delegates ignored Heldeyz, prone on the carpet before the Settler. There were half a dozen of them, mostly in the dress of wealthy merchants, one in Civil Government uniform. They threw themselves prostrate; a gesture that only the ruler of the Gubernio Civil was legally due. In fact, it was forbidden to any other on penalty of death, but the Governor was in East Residence, and Ali was very much present before their gates with fifty thousand men.

"Sovereign lord," the head of the delegation mumbled into the carpet; he was an elderly man, sweating in the heat, the wattles under his chin sliding down into the expensive but dust-stained silver lace of his cravat. "Spare us."

Well, thought Raj. That's straightforward enough.

"Surely," the alcalle of Gurnyca said, "we may make amends to Your Supremacy for any offense we have unwittingly given. We are but poor merchants, not the lords of State. We have no knowledge of high matters. Yet if wrong has been done you, we are willing to pay. Surely there can be peace—who would benefit from war?"

Ali smiled. "There may be peace, if God wills. There is but one God, and all things are accomplished according to the will of God." He nodded, and added in his own tongue: "Salaam, insh'allah."

One ringed hand stroked his beard, and he flicked a finger at a clerk. "You spoke of payment. The tribute from you kaphar ingrates is in arrears to the extent of—"

"—twenty-one hundred thousand gold dinars, O Lion of Islam," the clerk said. "That is not counting interest on late payments at—"

"Silence," Ali purred, a lethal amusement in his voice. "Am I a merchant, to haggle? By all means, if this is made good, let there be peace."

Even under the Colonial guns, that brought a wail of protest. "Lord, Lord," the alcalle said. "We are but one city! There is not that much gold in all Gurnyca, not if we stripped the dome of the cathedron and the fillings from our teeth."

"Both of which," Ali pointed out genially, "will be done if the city is put to the sack." He raised a hand. "It is the time of prayer. Surely, we may speak again of this later; and you shall return to your city with an escort and safe passage. In the morning, I shall give my final decision."

The scene shifted, the sun dropping toward the horizon and both moons high, looking like translucent glass against the bright stars. Date palms and orange groves stood in darkening shadow as the Gurnyca elders and Heldeyz rode their dogs through the belt of irrigated land surrounding the city. Water chuckled in the canals that bordered the fields, oxen lowed, but there was no sight or sound of human beings, no smoke from the whitewashed huts of the peasantry. Fields lay empty, scattered with tossed-aside hoes and pruning hooks; a manor stood ghostly among its gardens, with only the raucous sound of a peacock strutting along the tiled portico.

Frontier reflexes, Raj thought grimly. They know when to make a bolt for the walls.

There were no buildings or trees within a half-kilometer of the fortifications, only pasture and field crops; and the city defenses were first-rate. Raj remembered them well from the archives, which he'd memorized long before Center entered his life. Modernized a century ago, and then again in his father's time. A clear field of fire, good moat, new-style walls sunk behind it, low and massive. Ravelins and bastions at frequent intervals, giving murderous enfilade fire all along the circuit, with a strong central citadel near the water. The guns were cast-iron muzzle-loaders like most fortress artillery, but formidable and numerous; there were some very up-to-date rifled pieces among them.

Resolutely held by a strong garrison, the city could have held for months against the Colonial army—and it would be impossible to bypass. Taking it by siege would require full-scale entrenchments, pushing artillery positions forward inch by bloody inch, escalade trenches, until enough heavy howitzers were close to the wall and you could pound it flat. Even then, storming it would be brutally expensive. By that time, the Civil Government would have had time to mobilize its field armies in the East and march to the city's relief. It was a strategy that had worked a dozen times in the endless eastern wars.

If the garrison was up to strength and competently led.

Center's viewpoint switched to the escort, a full half-battalion of them, two hundred and fifty men. They didn't look particularly impressive at first sight, dark bearded men, many with the tails of their pugarees drawn across their faces like veils. Raj looked for telltale signs: their hands, the wear on the hilts of scimitars and carbines, the way they sat their dogs, how often they had to check or spur to keep their dressing.

These lads have been to school. Their commander was a stocky man, one of the ones with the tail-end of his turban drawn across his face. Scars seamed the backs of his hands, and another gouged down from forehead to nose . . .

. . . and his eye was unmoving on that side. Tewfik. Raj cursed to himself. With a glass eye for once, rather than his trademark patch. He'd met the Colonial commander once, in a parley before the Battle of Sandoral, four years ago. What's he doing there? It was a job for a minor emir, not the commander-in-chief.

An image flickered through Raj's consciousness, tinged somehow with irony: himself, leading the 2nd Cruisers through the tunnel under Lion City's walls.

Point taken, Raj noted dryly.

The white dust of the road shone ruddy with the setting sun, streaked with the long shadow of the tall cypresses planted by its side. They came to the outer gatehouse of the city's defenses, where the highway crossed the moat on stone arches. Civil Government troops opened the iron portals: infantrymen, slovenly-looking even for footsoldiers. Raj ground his teeth at the rust on one man's rifle barrel. They eyed the Colonial troops with the prickly nervousness of a cat watching a pack of large dogs through a window. Heldeyz saluted their officer and opened his mouth to speak.

Tewfik drew his revolver and shot the man in the face.

A red spearhead seemed to connect the Arab's hand and the guard officer's nose for an instant, and then the footsoldier jerked backward as if kicked in the face by an ox. His helmet rang against the stone of the gatehouse, the last fraction of the clank lost in the snapping bark of carbines as the Colonials cut loose with their repeaters. They boiled forward, screaming in a wild falsetto screech. One of the Civil Government soldiers managed to get a round off, the deeper boom of his single-shot rifle painful in the confined space. Then he went down under a Colonial officer's yataghan, still stabbing upward with his bayonet.

The fight in the gateway lasted bare seconds, leaving Heldeyz and the city fathers sitting their dogs and gaping at the litter of bodies. Puffs of off-white smoke drifted by; the Colonials were wasting no time. Dozens of them stuck their carbines through gunslits in the doors and fired blind, as fast as they could work the levers, sending a lethal hail of the light bullets to ricochet off the stone walls within. Hand-bombs and axes pounded the doors open. The rest of the Colonial force formed a dense four-deep firing line at the inner gate, thumbing reloads from their bandoliers into the loading gates of their weapons. Heldeyz's head whipped around at the high shrill scream of a Colonial bugle.

Mounted men were pouring out of the orchards that ringed the city, spurring their dogs. The animals bounded forward at a dead run, covering the ground in huge soaring leaps as they galloped with heads down and hind legs coming up nearly to their ears on every jump. Rough hands threw the courier aside as the column poured into the strait confines of the gatehouse and broke out into the cleared ground beyond; a battery of pompoms followed, their long barrels jerking wildly as the gunners lashed their dogs. Iron wheels sparked on the paving stones, and behind them the roadway was red with crimson djellabas . . .

* * *

Barholm's fist hit the table as the courier's words stumbled into silence. He didn't have Center's holographic visions to flesh them out, but there was nothing wrong with his wits.

"They knew the wogs were there in force and they didn't keep a better guard than that?" he said.

"Sole Autocrat, the garrison was under-strength and badly trained," Raj said quietly. "In any case, they paid for their folly."

"Yes," Heldeyz said, his eyes remote. "They paid."

Observe, Center said.

* * *

The scimitar flashed in the sun. A heavy thack sounded, with the harsher wet popping of fresh bone underneath. The alcalle's head rolled free; his body collapsed from its kneeling position, heavy jets of arterial blood splashing into the reddish mud that stained the ground. Clouds of flies lifted, then settled again. The executioner flourished his heavy two-handed curved sword ritually.

The smoke from the burning buildings covered the smell, even from the pyramid of heads the Settler's mamluks were building beside the outer gate. Few of the chained coffles of Gurnycians marching out paid much attention to it; their faces were mostly blank, eyes to the ground. Mounted Colonial guards urged them on with snaps of the kourbash, the long sauroid-hide whip. They were the lucky ones: pretty women, strong young men, craftsmen, and children old enough to survive the trip south to the markets of Al Kebir.

Ali pointed. "No, cut that one's throat," he said, indicating a Star priest with a thin white beard. The executioner lowered his sword.

The old man's eyes were closed; he was praying quietly as the black-robed mamluk stepped up behind him and drew the curved dagger. Ali giggled when the body toppled thrashing to the ground.

"The halall," he said, sputtering laughter. The ritual throat-cutting that made meat clean for Muslims to eat. "Is it not fitting, for these beasts?"

Raj noted a mullah's lips tightening at the blasphemy. Nobody spoke.

The good humor on Ali's face turned gelid as he gripped Heldeyz's face in his hand and turned it to the heaps of severed heads.

"Do you see, infidel?" he screamed. "Do you see?"

A portly man in a green turban shoved his way through the crowd. A string of prisoners followed him, mostly girls in their early teens, with a few younger boys. He prostrated himself.

"Oh guardian of the sacred ka'ba, you wished—" he began in a falsetto voice.

Ali released the Civil Government courier. "Yes, yes," he said impatiently. His hand flicked to a girl and a boy. "Those two, and don't bother me again before the evening meal." He jerked his head at his guards. "Come. Bring the pig-eating kaphar."

Wagons took up most of the roadway, oxen lowing under the load. Inside, in the cleared space within the walls that Civil Government law commanded, were huge heaps of spoils; officers were directing the troopers as they piled it in neatly classified heaps. Cloth, metalware, tools, coin, precious vessels from the Star churches and temples . . . Beyond, only a few buildings still stood. As Heldeyz watched, a merchant's townhouse collapsed inward about the burning rafters, the thick adobe walls crumbling like mud. A ground-shaking thump, and the great dome of the Star temple followed; Raj recognized the sound of blasting charges.

"See, unbeliever," Ali went on. "The pig and son of pigs Barholm—it was not enough that he cheated me of the blood-price of my father's death, he expected me-me—Ali ibn'Jamal, to sit among the women and do nothing while he conquered all the world. Conquered all the world, then turned on me! Turned on the Faithful! No, kaphar, Ali ibn'Jamal, Guardian of Sinar, Settler of the House of Islam, is not such a fool as that.

"Tell Barholm I am coming for him." Ali's mouth was jerking, and his voice rose to a shrill scream. "Tell him I have something for him!"

Colonial soldiers were setting a sharpened stake in the ground. They dragged out the Arch-Sysup Hierarch of the Diocese of Gurnyca. He was a portly man, flabby in middle age, stripped to his silk underdrawers. The black giants holding his arms scarcely lost a step when he collapsed at the sight of the waiting impaling stake . . .

* * *

Silence fell around the table. At last, General Klosterman cleared his throat.

"Well, I don't think there's much doubt as to Ali's intentions," he said.

Barholm nodded abstractedly. "General Klosterman, how long would it take to mobilize all available field forces and meet the Colonists in strength?"

Klosterman paled. Master of Soldiers was an administrative post, but it did give the elderly officeholder a good grasp of the state of the Civil Government's defenses.

"Lord, Ali has fifty thousand of his first-line troops with him. If we summoned all available cavalry, we couldn't field half that in time to meet him south of Sandoral, or even south of the Oxhead Mountains . . . and forgive me, Sovereign Mighty Lord, but the troops we could summon would not be in good heart."

Observe, said Center.

* * *

This time Center's projections started with a map. Raj recognized it, a terrain rendering of the Civil Government's eastern provinces. The Oxhead Mountains ran east-west, then hooked up northward; north of it was the sparsely settled central plateau, and to the south and east was the upper valley of the Drangosh and its tributary. That was densely settled in part, where irrigation was possible; elsewhere arid grazing country, with scattered villages around springs in the foothills.

Colored blocks moved, arrows showing their lines of advance. He nodded to himself; so and so many days to muster, supplies, roadways, the few railroad lines. Twenty thousand men maximum, perhaps thirty thousand if you counted the ordinary infantry garrisons called up from their land grants. And . . .

Men in blue and maroon uniforms fled, beating at their dogs with the flats of their sabers or with riding whips. A ragged square stood on a hill, with the Star banner at its center. Black puffballs of smoke burst over the tattered ranks, shellbursts, and Colonial field guns hammered giant shotgun blasts of canister in at point-blank range. Men splashed away from the shot in wedges. A line of mounted dragoons drew their scimitars in unison, flashing in the bright southern sun. Five battalions, Raj estimated with an expert eye. Twenty-five hundred men. Trumpets shrilled, and the scimitars rested on the riders' shoulders. Walk-march. Trot. The blades came down. Gallop. Charge. A single long volley blew gaps in their line, and they were over the thin Civil Government square. The Star banner went down. . . .

* * *

"Lord," Klosterman went on, "with humility, my advice is that we throw as many men into Sandoral and the eastern cities as we can. Ali cannot take them quickly."

Tzetzas spoke for the first time. "But he could bypass them," he said.

Raj nodded silently, conscious of eyes glancing at him sidelong.

Observe, said Center.

* * *

From horizon to horizon, the land burned; ripe wheat flared like tinder under the summer sun, sending clouds of red-shot black into the sky. Denser columns marked the sites of villages and manor-houses. In an orchard, peasants worked under Colonial guns, ringbarking the trees and piling burning bundles of straw against their roots.

A flicker, and he was outside a city: Melaga, from the look of the olive-covered hills around it. Raw red earth marked the siegeworks about it, a circumvallation with a high wall topped by a palisade. Zigzag works wormed inward from there, each ending in a redoubt protected by earth-filled wicker baskets. Swarms of men hauled cannon forward and dug at the earth. Guns boomed from the city walls, and men died in the siegeworks, but more took their places. Howitzers lobbed their shells into the sky, the fuses drawing trails of smoke and fire until they burst within the walls . . .

* * *

"No, that would be far too uncertain," Tzetzas went on. "Instead, well, the treasury is unusually full. We could offer Ali twice, three times the previous tribute."

Barholm snorted. "After we shorted him on the last agreement? I can just see him quietly going back to Al Kebir, demobilizing his army and waiting for the gold to arrive."

"Sovereign Mighty Lord," Heldeyz said, "he's not here for gold. He's here for blood. He's . . . he's not going to be bought off. You have to see him—"

Ali would agree to the increased tribute, but remain on civil government soil, probability 97%, ±2. Observe, said Center.

* * *

"Filth!" Ali screamed. He strode through the pavilions, kicking over platters filled with whole roast lambs, rice pillaus, fruits, and ices. "You call this a feast of welcome! Filth!"

The syndics of the town shrank backward, looking around with the instinctive gesture of men in a trap with no exit.

"That pig Barholm, that two-dinar Descotter hill chief who calls himself a conqueror, it isn't enough he makes me wait for my tribute, but he insults me too."

Ali stopped, smiled, relaxed. The expression was far more frightening than the bloodthirsty madness of a minute before.

"Well then, we'll have to show the kaphar what it means to insult the Commander of the Faithful, won't we?" he went on.

He eyed the assembled syndics with much the same expression that a farmwife would have, standing in the yard and fingering her knife as she selected a stewing pullet.

Observe:

A younger Ali knelt behind a girl. Gardens bloomed around them, thick with flowers and softly murmurous with bees; the stars shone above, the only light on the rippling water of the fountain save for a few discreet lanterns. Ali had a hand on the girl's neck, pushing her face below the surface of the water as he thrust into her. He let her rise for an instant, long enough to take one breath and scream.

It bubbled out as he pushed her down again. Her hands beat against the marble of the pool's rim, leaving bloody streaks on the carved stone.

Observe:

* * *

Ali sat at a chessboard, across from a grave white-bearded man. The pieces were carved from sauroid ivory and black jadeite; they played seated on cushions of cloth-of-gold, beneath a fretted bronze pergola that served as support for a huge vine of sambuca jasmine. A slender girl naked except for the filmy veil that hid half her face poured cut-crystal goblets full of iced sherbert. Droplets of condensation stood out on the silver ewer.

"Checkmate, Prince of the Faithful," the older man said. "Congratulations. This is your best game yet."

Ali looked down at the chessboard, his lips moving as he traced out the possible movements. When he moved, it was so swiftly that the serving girl had time for only the beginning of a scream.

His hand grasped the cadi's white beard, and the dagger slashed it across. He threw the tuft of hair in the older man's face.

"Sauroid-lover," he screamed. "You dare to insult me?"

The old man drew himself up. "You forget yourself, Ali," he said. "I am appointed by the Settler to guide your footsteps. You must learn restraint—"

Ali moved again, very quickly. The curved dagger in his hand was hilted with silver and pearls, but the blade was layer-forged Sinnar steel, sharp enough to part a drifting silk thread. It sliced more than halfway through the cadi's throat. The old man turned, his blood arching out in a spraying stream of red across the priceless silk of the cushions and the white body of the girl. Ali stood silent, panting, watching the body tumble down the alabaster steps of the gazebo. Then he turned toward the servant, smiling. Blood ran down his mustaches, and speckled his lips.

Observe:

* * *

Ali sat on the Peacock Throne of the Settlers, in a vaulted room whose ceiling was an intertwining mass of calligraphy picked out in gold, the thousand and one names of Allah, the Merciful, the Lovingkind. From a glass bull's-eye at the apex, light streamed down, mellow and gold, to the tessellated marble floor. Guards stood motionless around the walls of the great circular chamber. Others dragged a man forward; he was stripped to his baggy pantaloons, a hard-muscled man in his thirties with a close-cropped beard and a great beak of a nose.

"Greetings, Akbar my brother," Ali called jovially. "How good, how very good to see your face again!"

The Settler's brother drew himself up and spat on the marbled floor. "You have won, Ali," he said disdainfully. "Yours is the Peacock Throne. Bring out the irons and have done."

"Irons?" Ali said.

That was the traditional punishment for the losers, when a dead Settler's brothers fought for the throne. Only a man complete in his limbs and organs could be Commander of the Faithful; Tewfik was disqualified because he had lost an eye in battle. A red-hot iron fulfilled the same purpose.

"Irons?" Ali said again. "Oh, may Allah requite me if I should put out the eyes of one born of the same seed, of Jamal our father."

Eunuchs brought out a stout iron framework, like a high bedstead with manacles at each corner. Akbar began to bellow and thrash; the guards held him down with remorseless strength while the plump, smooth-faced eunuchs snapped the steel cuffs around wrist and ankle.

"Shaitan will gnaw your soul in hell if you shed a brother's blood!" Akbar yelled.

Ali stood and made a gesture. The guards saluted with fist to brow, and marched out of the great chamber.

"I? Shed your blood? Never, my brother."

Ali stood by the iron rack, stroking his beard. He pulled a handkerchief from one sleeve of his pearl-sewn robe and made as if to wipe his brother's face; when the other man opened his mouth to shout a curse Ali deftly stuffed the length of silk into it.

"There. It is unmannerly to interrupt the Settler. Do you not remember, brother, how you boasted to your captains during our brief, unfortunate civil strife—how you boasted to them that I should be sent into exile on an island in the Zanj Sea with only a mute crone to attend me? That a . . . how did you phrase it? A perverted bastard son of a diseased sheep like me did not deserve the delights of the hareem, and that the pearl-breasted beauties who served me would be shared among your amirs."

He clapped his hands. A line of women filed into the throne room, the long robes of their chadors brushing the floor and the sleeves hiding their hands.

Ali turned. "Zufika, Aisha," he said. "All of you—hide not the light of your faces."

Obediently, they dropped the filmy black cloaks to the floor. Several of them were carrying long slim knives; two bore a charcoal brazier between them, holding the metal frame with iron tongs. Others set a stool by the iron frame. Ali sank down with a satisfied sigh.

"No, I shall not shed a drop of your blood," he said. "But you surprise me, with this unseemly conduct. Don't you know it is unfitting for an entire male to look on the faces of the Settler's women?"

Zufika came forward, the knife in her hand. "Attend to it, my sweet one."

Through the gag, Akbar began to scream.

* * *

"Sovereign Mighty Lord," Raj said quietly.

Silence fell; even Barholm checked himself, dropping the finger he'd been wagging under Chancellor Tzetzas' nose.

"With your permission, lord, I'll take command in the East. Superseding the Commander of Eastern Forces and the garrison commandants."

There were nods all around the table, even from Gharzia. Right now the high command in the east was the sort of honor you took with you to an unmarked grave.

"And I'll take seven thousand cavalry to the border."

"Ridiculous—"

"That'll strip the garrisons of—"